Last article in this series on industrial mining. You can find the other parts here:

Part 1: Mining: An Environmental Catastrophe

Part 2: Mining: A Social Crisis

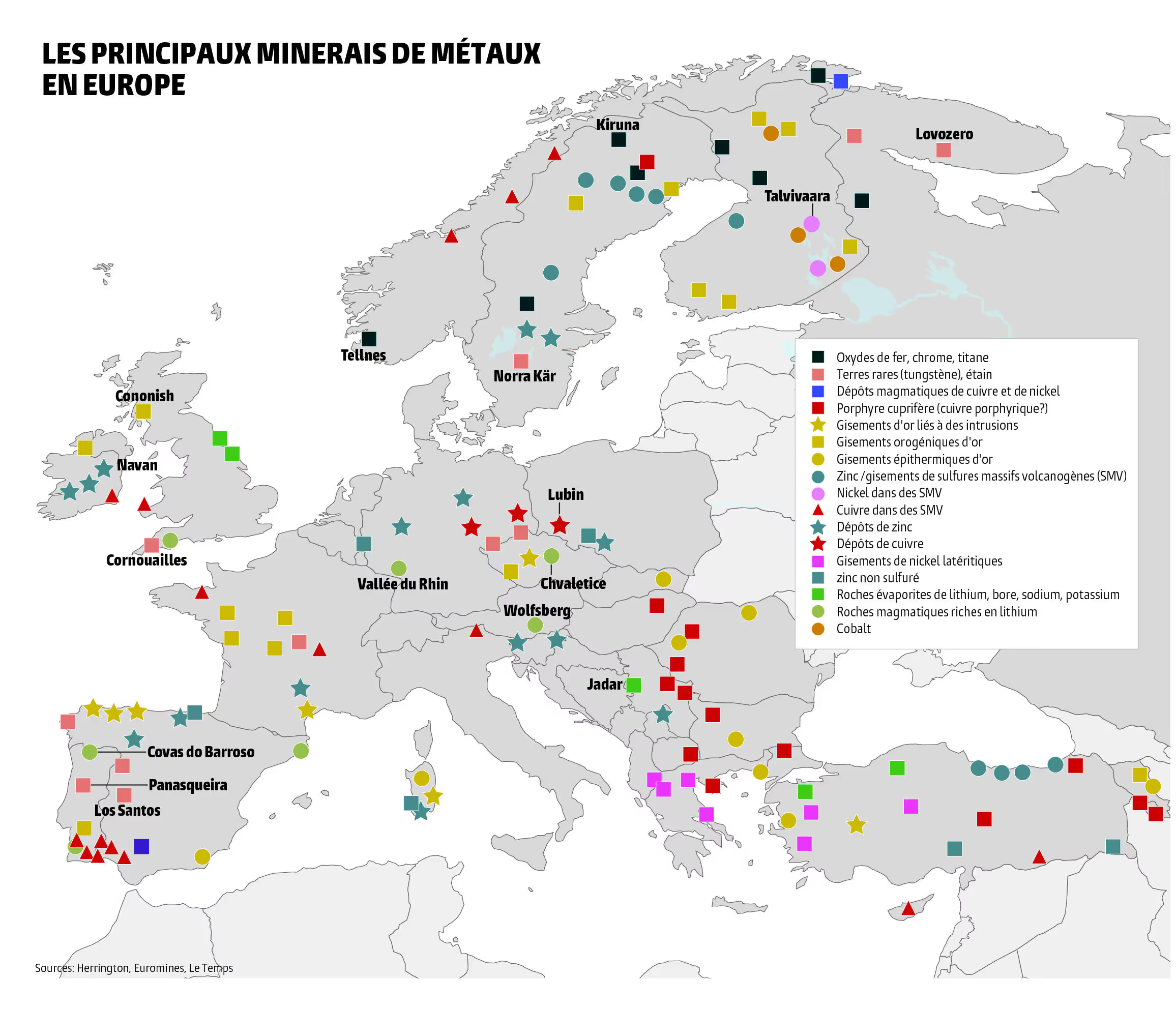

Part 3: The Return of Mining in Europe – When “Green” Hits Rock Bottom

<hr>

Part 4: Why Mineral Degrowth Is a Myth

While the analyses by Célia Izoard and the association SystExt are valuable for the ecological struggle, ATR disagrees on the strategy to adopt. Here, we focus primarily on Célia Izoard’s strategic proposals.

Her idea is to reduce overall metal consumption in the economy to lessen reliance on extractivism. According to her, this would require strong political measures, achieved through a power shift driven by social movements and the consultation of communities affected by mining projects[1].

Drawing inspiration from eco-Leninist Andreas Malm, Izoard proposes distinguishing between “subsistence extraction” and “luxury extraction” to combat mineral overconsumption. For example, ChatGPT and two-ton electric cars would be considered mineral overconsumption and would not meet essential needs. What counts as essential or non-essential could be determined by social justice movements or local citizen assemblies. Then, items categorized as luxury extractivism would likely be eliminated from the economy through strong political measures. This could include banning electric SUVs, which consume too many metals relative to their usefulness. There would also need to be legislation on the appropriate age for phone use (as if the State wasn’t part of the problem).

But let’s assume, just as an example, that such a program could be implemented (how? By whose interests? With what kind of “democracy”? What level of popular education? What practical applications? On what timeline?).

Picture yourself as a citizen invited to a local assembly, charged with discussing the question: “Which essential needs justify maintaining extractivism?” You come informed, having read Izoard’s book, which highlights why smartphones are neither socially nor environmentally sustainable. One passage, in particular, resonates deeply with you:

“It is clear that Fairphone[2] has been exploring every possible avenue for the past ten years to make the smartphone socially and environmentally acceptable. The fact that it has failed, or only succeeded marginally, leads to a harsh conclusion: the device is not viable. (…) Even with the best intentions in the world, it is simply not possible to produce an object containing more than fifty different metals under decent conditions[3].”

As a conscientious participant, you propose banning the sale of smartphones in France. However, other participants argue that smartphones are essential in modern life – for example, to secure bank transfers, navigate, stay in touch with children, or handle emergencies – and that such a ban would be unpopular[4]. Even if, miraculously, the proposal were adopted, it is very likely the government would refuse to submit it to a parliamentary vote (as was the case with most proposals from the Citizens’ Climate Convention[5]), since smartphones are vital to the functioning of the economy. Banning them would create a competitive disadvantage compared to other countries, potentially triggering crisis and unemployment. And who would willingly give up economic growth? Furthermore, such a measure would probably conflict with European regulations, making it unenforceable. Finally, imagining consensus among all countries to prohibit the production and sale of smartphones is pure fantasy.

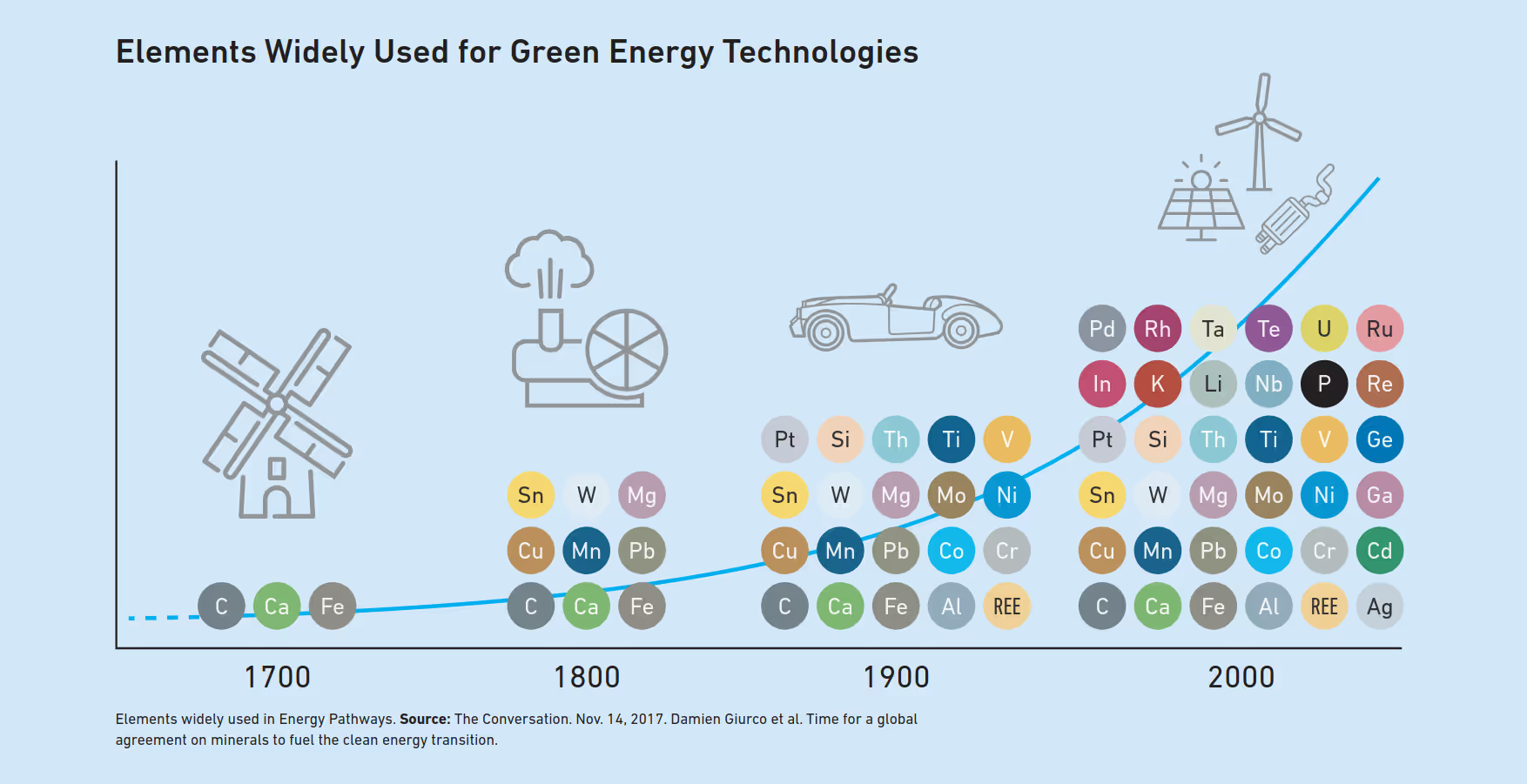

So there it is. You’ve just had a taste of the challenges that come with planning. Now you’re expected to start over – despite the vanishingly small odds of success – for every mineral, and for every product made from them. You’ll have to go through it all again for the television. Then again for the microwave. Again for the radio, the electric car, the washing machine, the smartphone, the heat pump, the photocopier, the lightbulb, the satellite, the MRI scanner, the aerospace sector, the radiator, the fridge, the computer... and on it goes. All while new products keep being developed, existing products become more and more embedded in society, and your workload grows and grows.

It seems that “bottom-up planning” ends up simply prolonging ecocide.

In other words, all these objects appear, regrettably, to fall under what Célia Izoard calls “subsistence extractivism.” But what happens when this so-called “subsistence” extractivism leads to water shortages and toxic pollution – just to manufacture washing machines? What if the subsistence of some depends on the dispossession – or the non-subsistence – of others?

ChatGPT has been cited by Célia Izoard as an example of “luxury extractivism” – a non-essential use of resources. Unfortunately, the current race for ever more powerful AI seems to rule out any form of regulation. Moreover, these technologies – which are considered strategic for both the economy and the military (AI, 5G, etc.) – are rarely subject to democratic consultation. In some countries, they are even designated as being of “national interest.” For example, France’s Citizens’ Convention on Climate once proposed a moratorium on 5G, pending better understanding of its impacts on health and the environment. But in September 2020, speaking to digital industry leaders, the French president Emmanuel Macron declared that France would embrace 5G, dismissing calls for caution as a desire to “go back to oil lamps” and mocking what he called the “Amish model.”

But this failure can’t be blamed solely on the President and his dismissive remarks. Abandoning 5G would mean sacrificing competitiveness – effectively dooming French companies in the face of global competition. No political leader, whether from the right or the left, would willingly make such a decision.

Democratically deciding which products should be kept and which should be phased out is a puzzle destined to fail – because the techno-industrial system is indivisible. All its components are deeply interconnected and cannot function independently of one another. Technological “layers” such as electrification and digitalization don’t simply stack on top of each other – they accumulate and intertwine. As a result, it’s impossible to abandon digital technologies while maintaining, for example, railway networks.

Moreover, global supply chains are far too long, complex, and dispersed to accurately determine the final uses of metals. Even the CEO of Fairphone – an “ethical” electronics brand – admits this.[8] After all, how can anyone trace the ultimate destination of copper extracted from the Rio Tinto mine in Spain, then smelted and refined in China, before being sold to industries all over the world?[9]

In addition, the wide range of potential uses for a single metal – as well as the simultaneous extraction of secondary metals – distorts any possibility of meaningful democratic debate around new mining projects. For instance, the public consultations surrounding the proposed lithium mine in Échassières (in the Allier region of France) highlight its role in electric battery production. But they fail to mention that lithium is also used in aerospace alloys to reduce equipment weight – or in missile warheads.[10] Nor do they disclose that this mine sits atop a deposit of beryllium – a metal more toxic than asbestos, yet considered strategic for the defense and aerospace industries.[11]

Thus, even the most well-intentioned measures are incapable of addressing the problem. Even if a “good” government were, one day, to successfully impose a ban on electric cars or restrict smartphone use among children, such actions would carry little weight against the global surge in demand for metals.

Conclusion

To summarize, mineral degrowth – like degrowth in general – runs up against three fundamental barriers:

an economic impossibility, due to the inability to fully control globalized production chains;

a geopolitical impossibility, rooted in the economic and military competition between states and corporations;

and a technical impossibility, because of the deep interdependence between all components of the techno-industrial system.

If extractivism is to be fought, it won't be through “metal audits,” engineers “leading by example,” “low-tech computing,” better-paid children in Fairphone’s “responsible” mines, appeals to industrial conscience, collectivization, legal action, or symbolic gestures.

To dismantle the mining hellscape that threatens life on Earth monster, the only real option is the total dismantling of the techno-industrial system itself.