This article follows the first two parts covering the social and environmental impacts of industrial mining. The other articles can be found here:

Part 1: Mining: An Environmental Catastrophe

Part 2: Mining: A Social Crisis

Part 4: Why Mineral Degrowth Is a Myth

<hr>

Part 3: The Return of Mining in Europe – When “Green” Hits Rock Bottom

"Between 2002 and 2008, the price of metals – all types combined – tripled. US and European leaders then realized the extent of their dependence and the threat hanging over their supplies. The hegemony was outright plundering, but it was also a dependence disguised by the asymmetry of power.[1]"

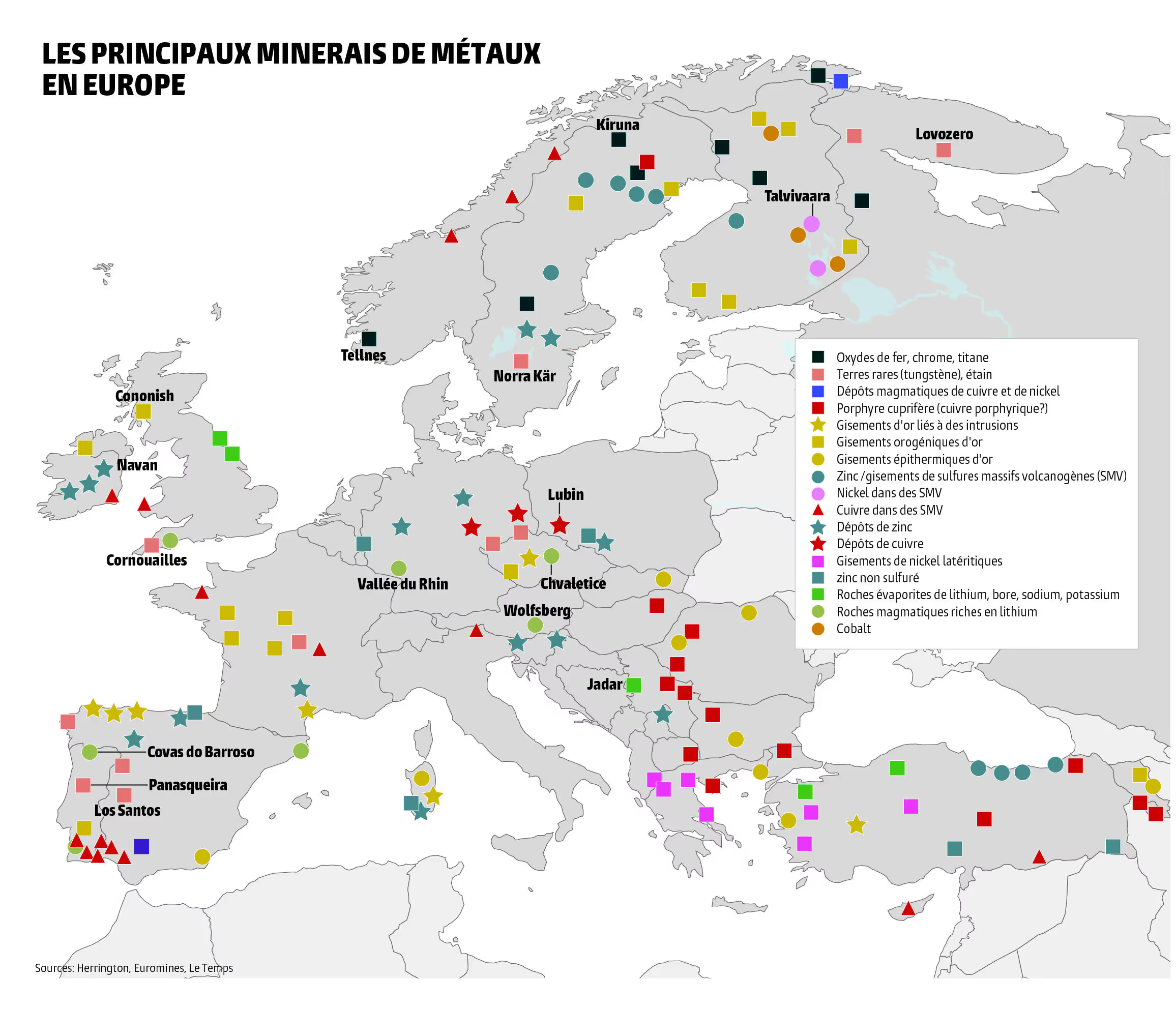

As mentioned earlier, most mines were relocated to so-called “Global South” countries starting in the 1980s. However, since the 2000s, Western countries have become aware of their vulnerability to China, a true “global mining empire[2].” Facing threats to their digital, automotive, aerospace, and defense industries, Europe and the United States decided in the 2010s to revive mining activities on their own soil to reduce their dependence. This shift was notably marked by the European Commission’s Raw Materials Initiative in 2008[3].

However, European and American leaders face a major challenge: mining has a bad reputation, and local communities strongly oppose having mines near their homes – even if it’s to produce planes and weapons “made right here.” Mining projects launched in France in the 2010s encountered fierce resistance and ultimately failed[4].

Yet, thanks to the power of greenwashing, the public has been persuaded to accept the return of mining in Europe. The so-called “energy transition” – aimed at replacing fossil fuels with renewable sources like wind, solar, and hydro – demands a massive surge in metal consumption. In fact, “for the same power output, an offshore wind farm requires ten times more metals than a gas-fired power plant, and an onshore wind farm seven times more[5].” It is estimated that “by 2040, the annual lithium demand from electric vehicles alone will be eight times the current global mining production[6].” This creates a compelling case for reopening mines across Europe.

“The transition involves shifting from fossil fuels to metals, which are non-renewable. In the best-case scenario – meaning if it truly results in a substitution of fossil fuels rather than an addition, as some fear – it would essentially transfer the energy demand previously met by oil, gas, and coal onto metals.”

For the sake of the “transition,” political institutions like the European Commission promote so-called “relocated” and “responsible” mining to produce the metals needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change. We are told that leaving poorly regulated mines in the “Global South” to supply batteries for European electric cars is criminal. Relocating mines to our own soil means greener mines that better respect human rights. It also means taking full responsibility for the mining impact of our consumption.

These arguments sound commendable – but unfortunately, they are misleading. First, opening mines in Europe does not mean closing others elsewhere. Northern mines do not replace Southern ones; they complement them to meet the skyrocketing demand for metals. Second, the unequal ecological exchange – the exploitation of cheap nature from the peripheries for the benefit of economic centers[8] – is reproduced within Europe itself: for example, mining in Swedish Lapland on the ancestral lands of the Sámi people, or in the Balkans, where billions of Euros have recently been allocated by the EU to mine vast quantities of metals, including a lithium deal with Serbia which has been criticized by its people as “turning Serbia into a mining colony”[9]. Finally, European mines are just as harmful as those elsewhere, using the same processes and consuming comparable amounts of water and energy.

“Opposing local mines to foreign mines ignores the systemic dead-end in which industrial mining finds itself. It’s somewhat like claiming that pesticide-sprayed monocultures are more sustainable in Europe than elsewhere. A mine can be more or less secure depending on regulations, but the determining factor remains the ore grades in the deposits. The lower the grades, the larger the volume of waste produced. The fact that these mines are located on European soil does not make disappear the tailings lakes, water contamination, droughts, and extreme weather events[9].”

This myth of the “responsible” mine and the “energy transition,” though false, is nonetheless very useful to justify reopening mines to meet the strategic needs of European industries. The digital sector in particular consumes ever-increasing quantities of metals. These metals require high purity levels, which in turn demand increasingly intensive refining processes involving water-intensive chemical treatments.

“Each year, over a billion smartphones roll out of Asian factories, along with tablets, computers, printers, scanners, consoles, and the entire big data infrastructure with its millions of servers, cables, and antennas – all of which require almost the full range of metals. Although these metals are used only in tiny amounts in each device, the sector’s exponential growth means the total volumes needed are rapidly increasing[10].”

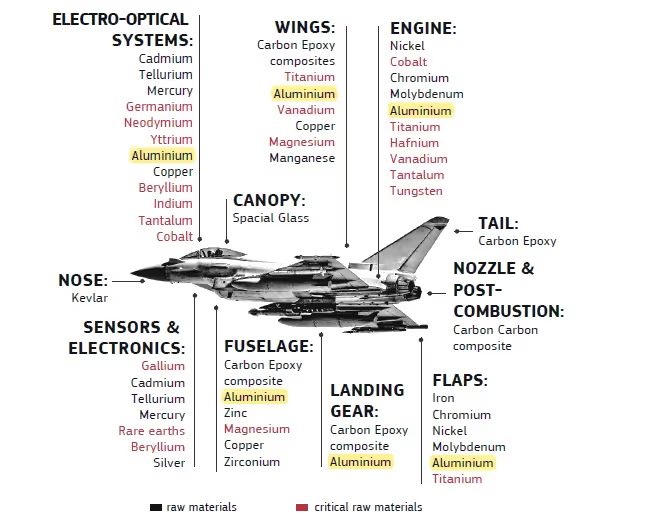

The same applies to the arms and aerospace sectors, whose demand for metals continues to grow. Indeed, the variety of metals used has steadily increased – from about ten metals used in weaponry during World War II to around fifty different metals today. The equipment itself has also become much larger, and consequently, the amount of metals required has soared: “(...) the Renault tank from World War I weighed 6.7 tons; the M1 Abrams tank used by the U.S. military since 1978 weighs ten times more, at 63 tons[11].”

“Here is, in summary, the vicious circle that states have begun to trap themselves in over the past decade: the rush for metals militarizes relations between nations, fueling the rush for metals to produce weapons in order to gain the means to seize more metals. This is the logic behind the escalating militarization between the United States and China, and vice versa. The more great powers prepare for conflict by securing strategic deposits, the more they push us toward war[12].”

What’s particularly convenient is that the “mines for the transition” also produce the metals needed for digital technology, weapons, and aerospace! For example, the lithium mine planned to open in 2028 in the Allier region sits on a deposit of beryllium, a metal more toxic than asbestos but crucial for the aerospace and defense industries[13]. No doubt this fact is less marketable than the promise of producing batteries to save the planet.

The mining industry is clearly treating us like fools, trying to hide weapons and computers behind “green” electric cars.

So, faced with all this, what’s the solution?

Célia Izoard and SystExt propose planning a reduction in overall metal consumption – a noble idea, but one that’s economically and geopolitically unrealistic. This is what we will explore in the final article.