Second part of the series of articles exploring the mining nightmare.

The other articles are available here:

Part 1: Mining: An Environmental Catastrophe

Part 3: The Return of Mining in Europe – When “Green” Hits Rock Bottom

Part 4: Why Mineral Degrowth Is a Myth

<hr>

Part 2: Mining: A Social Crisis

“Extractive industries are also accused of most of the worst abuses, which can even amount to complicity in crimes against humanity. Among these abuses are actions committed by public and private security forces tasked with protecting corporate assets, widespread corruption, violations of workers’ rights, and a broad range of abuses affecting local communities, especially Indigenous peoples[1].”

The first victims of mining are the workers. Considered by the International Labour Organization[2] as the most hazardous employment sector, mining claims many lives. Numerous workers suffer accidents or illnesses – often cancers and respiratory diseases – caused by exposure to toxic substances such as arsenic, cyanide, lead, mercury, and others.

In Morocco, Célia Izoard conducted an investigation into the cobalt mine of Bou-Azzer, which is certified as “responsible” by the Responsible Minerals Initiative, an organization that includes the well-known “ethical” smartphone company Fairphone[3]. The working conditions there are grueling, and the mine is contaminated with arsenic, causing “skin, lung, and bladder cancers, neurological and cardiovascular diseases, as well as reproductive disorders[4].” The widespread use of subcontracting strips many workers of their rights – they lack health insurance, paid leave, and retirement benefits. Fatal accidents deep inside the mine are unfortunately common.

“Workers diagnosed with stage 2 silicosis are generally fired, receiving a ‘compensation’ equivalent to two years’ salary on the condition that they do not report their illness. Many former miners and local residents suffer from cancers, as well as ‘new, unknown diseases’ that they cannot afford to have diagnosed. ‘All my uncles and their sons who work at Bou-Azzer are sick,’ laments a shopkeeper from Agdez. ‘One of my uncles receives a pension of only about one hundred euros after twenty years in the mine[5].’”

Worse still, any rebellion against this modern slavery is brutally crushed by the Moroccan state. In 2011, a large-scale strike broke out demanding better working conditions. “The strike ended with beatings and torture sessions at the gendarmerie, prosecutions, and imprisonments for ‘work disruption.’ Eighty unionized miners were fired, and others were only allowed to return to work on the condition that they leave the union[6].”

Despite the hellish working conditions at Bou-Azzer, many people endure them because agriculture nearby is impossible due to water scarcity caused by the mine. Water is pumped from the groundwater to process the ore, threatening the water supply for local communities.

“As Managem increases the number of boreholes to process the ore, there is less and less water available for the village, and the new borehole is now ten kilometers from the homes. In summer, the water supply is cut off for several hours each day. ‘We are the walking dead,’ declares Mustapha. ‘Soon, there won’t be any water left. Is this what they call sustainable development?’[7]”

Unfortunately, the Bou-Azzer mine is not an exception – it is the rule. The mining sector is considered one of the most hazardous for human health due to contagious substances, and many mines threaten the water supply of local communities. According to a 2021 study, 90% of mining areas suffer from water scarcity[8]. For example, in Chile, the El Soldado copper mine has depleted aquifers, forcing farming families in the nearby commune to leave due to a lack of irrigation water and contamination of tap water by toxic metals. The mining company will supply water by tanker trucks until 2027, in exchange for expanding its tailings storage facility[9]. These water problems are worsening due to two factors: declining ore grades, which require increasing amounts of water for mineral processing, and climate change, which is likely to intensify drought events.

Women are also particularly affected by the mining nightmare. Violence against women and prostitution tend to increase in mining regions due to the influx of workers from other areas.

“In this regard, Cunha and Casimiro (2021) gathered testimonies from women describing the changes brought by the establishment of the Montepuez industrial ruby mine in Mozambique. They report a massive influx of men from Mozambique and neighboring countries, whose behavior towards women has been extremely aggressive, including frequent acts of harassment, abuse, and rape[10].”

Despite its dramatic nature, the human tragedy of mining remains largely absent from Western imagination. When people think of mines, they often picture 19th-century coal mines – barbaric relics of a bygone era. Yet, this monstrous exploitation still persists, just no longer on our soil. The wave of offshoring in the 1980s shifted the majority of mining operations to so-called “Global South” countries, pushed to the margins of the industrial system. Out of sight, out of mind. This transfer was made possible by colonial powers and their neoliberal policies in the 1980s[11].

This domination is also enforced through Western (as well as Russian and Chinese) multinational corporations. These companies employ private security forces to suppress protests or directly call upon local police and military. The methods of repression are brutally violent: criminalization of activists, sexual assaults, arbitrary detention, torture, and assassinations.

Indigenous peoples are especially affected, and these projects often threaten their very survival. For example, in the state of Chhattisgarh in eastern India, the mobilization of Adivasi indigenous communities against industrial iron mines was met with violent repression by police and paramilitary forces, including arbitrary detentions, torture, and sexual assaults on women.

This is the true cost behind European smartphones and washing machines[13]. Outsourced violence and exploitation allow people in industrialized nations to enjoy their technological comforts, all while being comforted by the soothing myth of a “dematerialized world.”

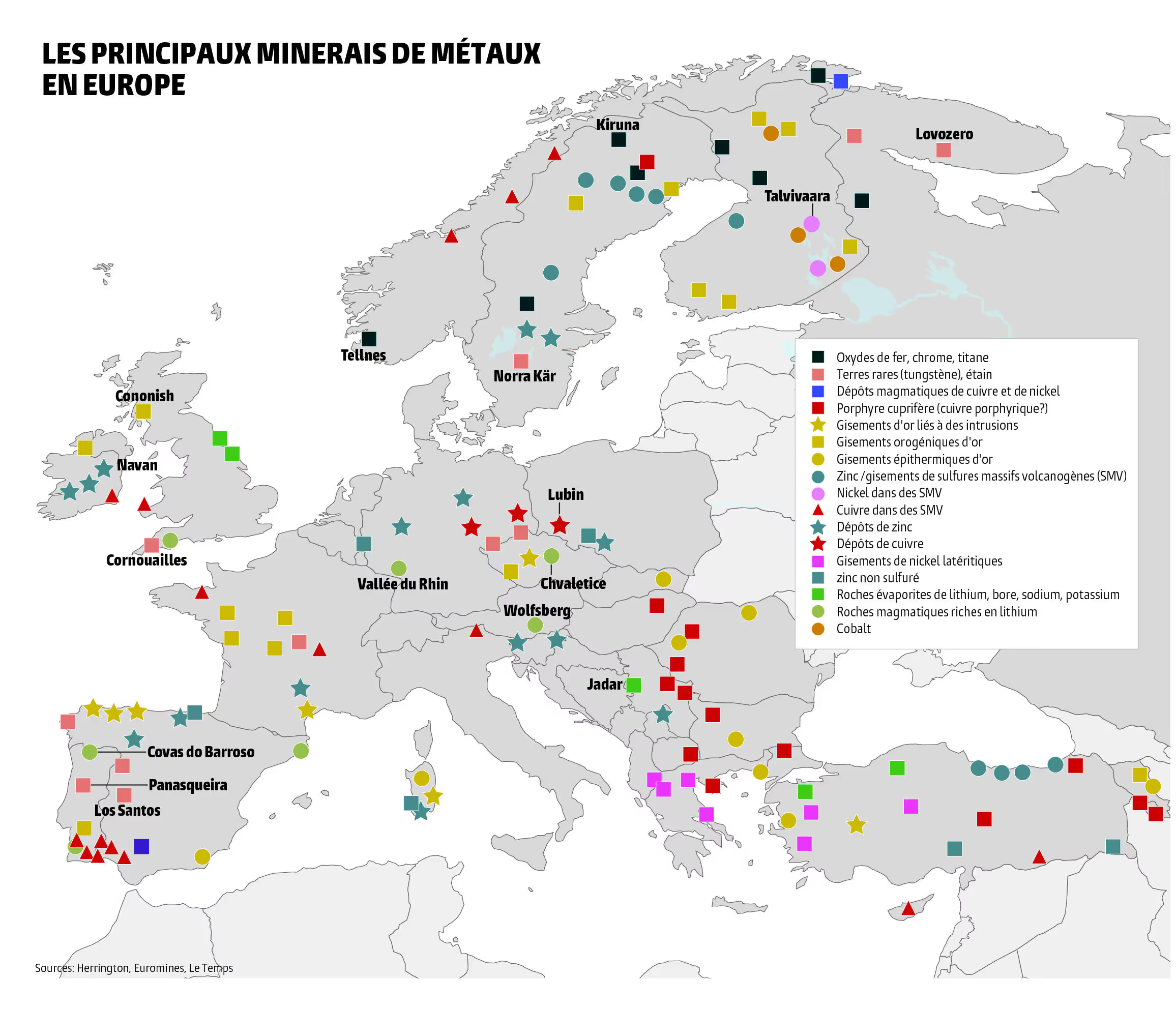

Today, this global dominance has morphed into a dangerous dependency – especially on China. In response, Western countries are pushing to restart mining operations in Europe and the U.S., all in the name of the so-called “energy transition.”

But ATR stands firm against every mine – no matter where it is or what promises it makes.