“The radical nature of industrial mining lies in the fact that it cannot coexist with life—neither with human worlds nor with non-human life[1].”

The mine is the beating heart of the industrial system. It forms the foundation of all the infrastructure and objects around us, from roads and buildings to cars and railways.

“Industrial capitalism is based on the exploitation of the earth’s underground resources—whether coal, gas, or oil (‘rock oil’), sand, or metals. Every object around us comes from the mine: from the mineral acids and titanium dioxide used to whiten the paper piled on my desk, to the light bulbs that illuminate my room, from the screen I’m looking at to the plastic bag I’m about to open[2].”

Everything discussed here is essential to the daily life of industrialized countries.

This article series is based on the french book The Mining Rush of the 21st Century: Investigating Metals in the Age of Transition by Célia Izoard, and from the first volume of SystExt’s report Mining Controversies: Debunking Common Myths About Mines and Mineral Supply Chains. We recommend these for anyone who wants to help defend the environment today — No serious strategic discussion about the environment can move forward without first confronting the uncomfortable truths revealed in these works. They expose, in detail, the deeply destructive material foundations on which industrial society is built.

Mining did not begin with industrialization. The Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, mining became “the heart of the economy” [3] in industrialized nations. Technological innovations — such as the rise of the railway and the expansion of manufacturing industries — depended entirely on a steady supply of mineral resources. Mining thus entered a radical new phase: an era of mechanized mass production targeting deeper, lower-grade, and more complex ore bodies [4]. This shift was made possible by the development of new extraction techniques, including increased mechanical power and hydraulic placer mining — a method that uses high-pressure water to erode rock or stir up sediments in alluvial deposits [5].

Since then, the machines used in mining have become increasingly larger and more powerful, allowing for even greater extraction volumes and the exploitation of ever-larger areas. For example, in the Rio Tinto copper mine studied by Célia Izoard, around 15 million tonnes tonnes of ore were extracted annually in 2023, compared to 7 million tonnes in 1997 — and 900,000 in 1880[6].

The human and environmental devastation caused by these massive mining operations matches their colossal scale. This article will explore the issue in four parts:

Part 1: Mining: An Environmental Catastrophe

Part 2: Mining: A Social Crisis

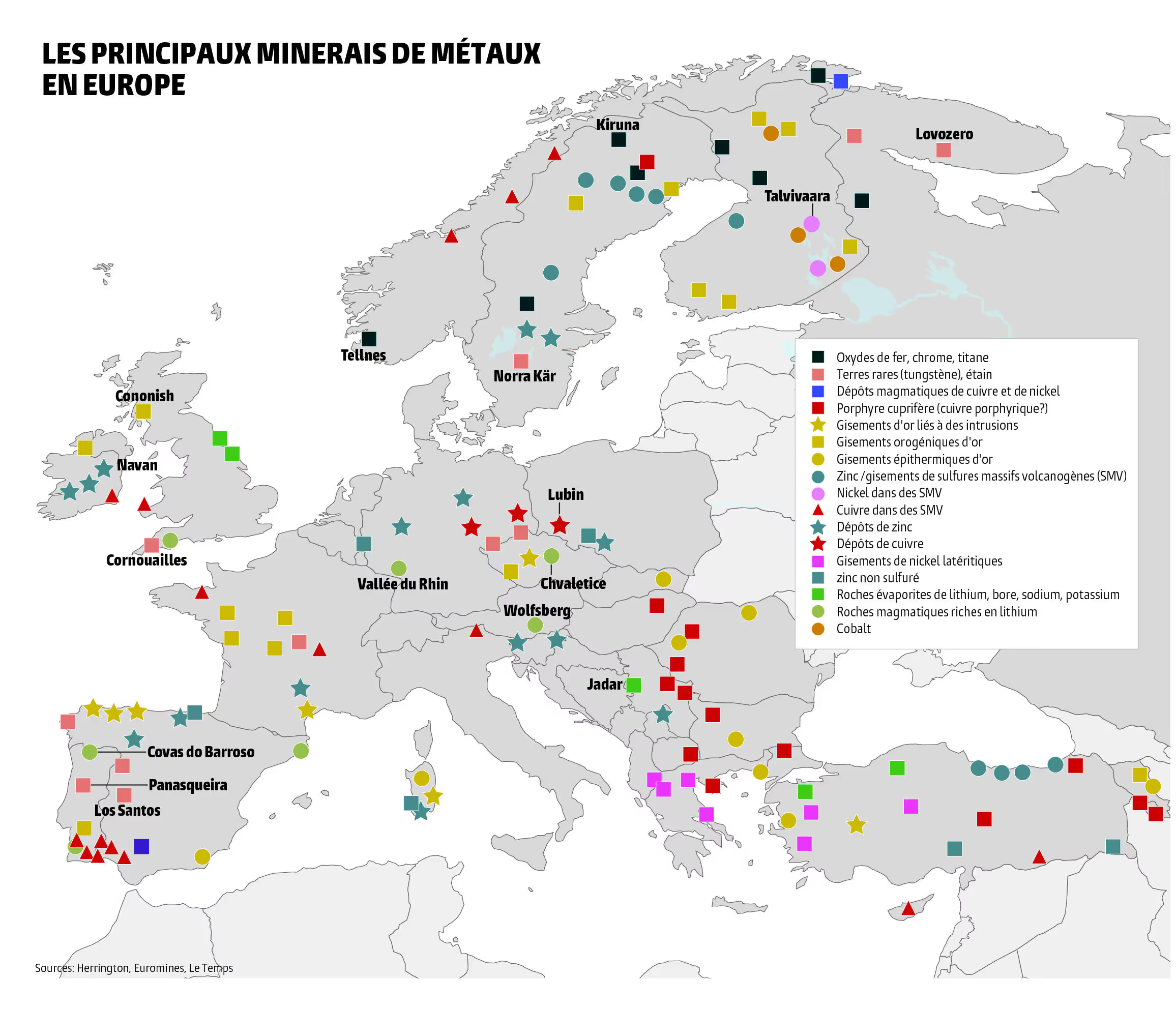

Part 3: The Return of Mining in Europe — When “Green” Hits Rock Bottom

Part 4: Why Mineral Degrowth Is a Myth

<hr>

Part 1: Mining: An Environmental Catastrophe

"By digging ever larger pits and filling entire valleys, extractive companies have become the most active geomorphic agents on Earth, surpassing the natural processes that have shaped the planet’s surface until now. Geologists have observed that each year, mineral extraction moves three times more material across the Earth’s surface than all the world’s rivers carry to the oceans[7]."

The immense scale of mining is first and foremost explained by an unchanging geological fact: nearly all metals are rare substances, present in just a few grams—or even milligrams—per ton of rock[8].

This means that a staggering and highly energy-intensive amount of material must be moved to extract just a few grams of valuable metal. The Rio Tinto mine perfectly illustrates this absurdity: the deposit contains only 0.4% chalcopyrite (the ore from which copper is produced). Yes, that means 99.6% of the extracted rock is waste, left behind on site! Known as “tailings,” these piles of rock form hills that release toxic substances into the air and water.

“The problem is that the amount of waste produced by mines today is incomparable to that of the past. Not only have extraction volumes increased dramatically, but ore grades have steadily declined. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Rio Tinto Company mined copper at a 2% grade; today, Atalaya Mining operates the site at just 0.4%. Meanwhile, current production levels are fifteen times higher than they were back then. In just over a century, the volume of waste generated has increased seventy-fivefold[9]!”

The second fundamental geological reality is that the sought-after ore is never isolated within the rock. Its extraction inevitably releases other metals — many of which are highly toxic to human health and all living organisms — such as arsenic (As), antimony (Sb), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg)[10]. For instance, in French Guiana and Bolivia, gold mining mobilizes mercury trapped in the soil, resulting in widespread contamination of local communities[11].

Once the ore is extracted, it must be concentrated through mineral processing, separating it from the other minerals present in the rock. In the case of copper from the Rio Tinto mine, the ore is crushed into a powder “the size of flour grains”[12] — a process that requires a tremendous amount of energy. It is then subjected to a series of chemical baths that allow the copper-bearing minerals to float to the surface. The “residues” from this phase — a toxic slurry of chemicals and metal powders — are then stored in massive tailings ponds, held in place by waste rock dams.

“At the four corners of these ponds, pipes continuously discharge flotation plant residues at a rate of ten million tons per year. Until the early 1970s, this was a valley; today, it has become an open-air chemical dump, similar to those found at mines worldwide. The residues have piled up to a depth of 100 meters and cover nearly 600 hectares[13].”

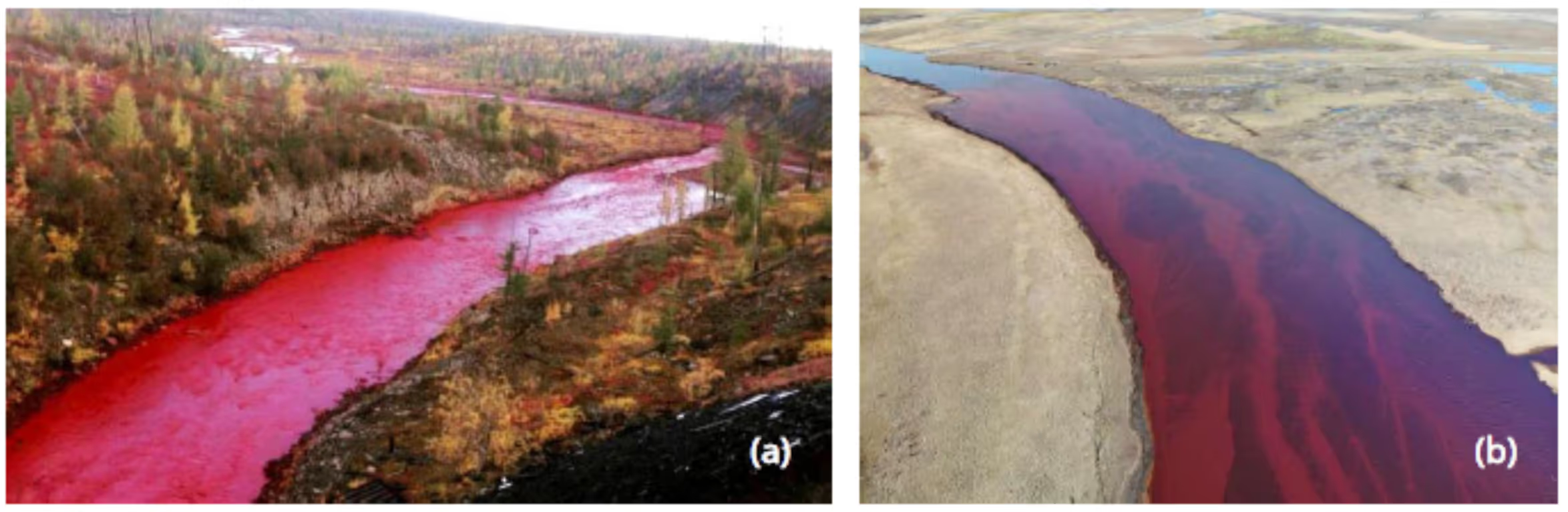

These massive toxic lakes can contain metals like lead and arsenic, as well as hydrocarbons and acids. Known as “tailings ponds,” they are the most polluting and hazardous infrastructure found at mines. Leaks into groundwater are common, and the risk of dam failures — resulting in devastating floods of toxic sludge that can sweep across entire regions or even countries — is very real. For example, in 2019 in Brazil, the dam at the Brumadinho iron mine collapsed, unleashing a mudflow of 12 million cubic meters that killed 270 people and destroyed a bridge, a village, and the surrounding wildlife and vegetation over tens of square kilometers[14].

Unfortunately, these accidents are all too common and stem from the very nature of these tailings ponds. And with the increasing frequency of extreme weather events due to climate change, these structures are becoming especially vulnerable:

“(...) Combined with the scale of modern mining, the extreme weather events driven by climate change could trigger cascading effects. Since the beginning of the 21st century, while the climate crisis is still accelerating, more than fifty tailings dam failures have already been recorded. How can the safety of these massive waste dams be ensured against torrential rains or cyclones? How will entire regions cope with drought if their groundwater and surface water have been contaminated by toxic residues[15]?”

Let’s set aside these vast toxic lakes and return to the copper concentrate obtained at the end of the mineral processing stage. Shipped to China, it is heated in large furnaces at smelting plants to produce “metallic blocks containing about 98% copper[16].” These smelters release sulfur dioxide, a toxic gas harmful to inhale and a major cause of acid rain.

Finally, the copper undergoes refining through electrolysis — once again immersed in a bath of copper sulfate and sulfuric acid, where an electric current separates the copper ions from other elements. The copper emerges from this process at 99.99% purity and can be used to manufacture plates, coils, and cables. However, for electronic applications (computers, phones), the copper must be even more refined — up to 99.9999% purity.

Studying the copper extraction process clearly exposes the fundamental unsustainability of industrial mining. These operations devastate everything in their path, drain groundwater reserves while contaminating what remains, destroy the habitats of countless species, and disperse metals capable of annihilating all forms of life. With the current push for “renewable” energy dependent on tearing vast amounts of metals and rare earth minerals from the soil, we should ask ourselves: Is this really a "green" transition?

The consequences are not just local but global. Mining accounts for about 8% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions and is the largest producer of solid, liquid, and gaseous waste. The massive toxic sludge lakes they generate rank among the largest man-made structures on Earth—and can devastate entire countries if a dam fails[17].

Regulating or nationalizing industrial mines will not solve the problem: they are inherently harmful and cannot coexist with humans, animals, or plants. If the choice is between mining and life on Earth, ATR chooses life.

No mines, no industries — neither here nor anywhere else.