We have reproduced this speech by the technocritical thinker Lewis Mumford delivered in New York on January 21, 1963. It was published in the journal Technique and Culture, vol. 5 no. 1, winter 1964 (ed. John Hopkins University Press). French translation by Annie Gouilleux, February 2012. You can find this text in a brochure published by Bertrand Louart and available for download on his Blog.

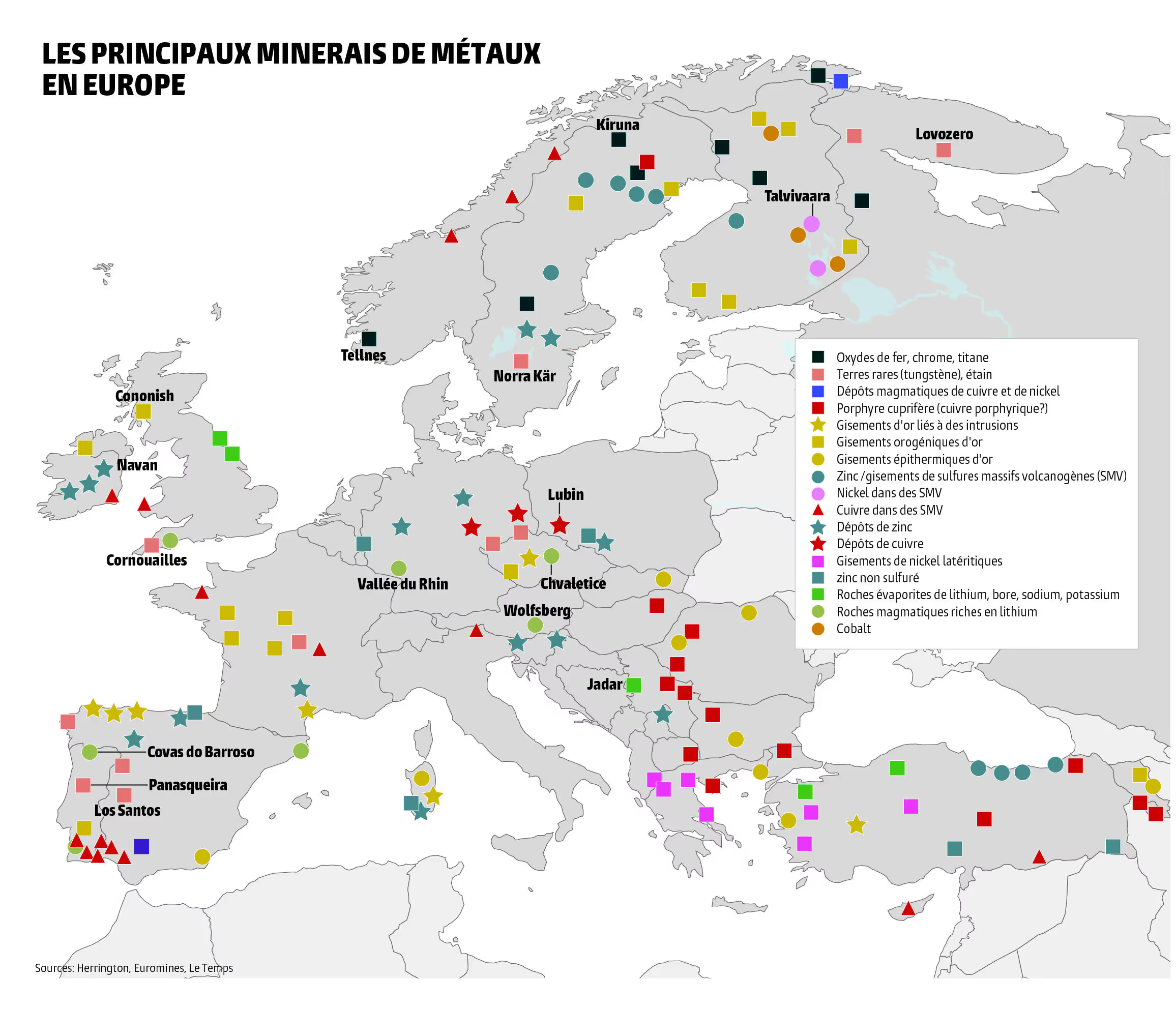

On the left in the illustration photo, a nuclear power plant, the most authoritarian technique there is. A technique as powerful as nuclear power cannot exist without a technical, scientific, industrial and military elite; without a State that closely monitors and controls its population reduced to the state of subservient cattle. On the right, a watermill. Used since ancient times to mill cereals, this democratic technique is not very powerful, ecological (low or even non-existent impact on the river ecosystem) and can be appropriated at the scale of a village.

“Democracy” is a word whose meaning is now confused and complicated by the abusive use that is made of it, often with condescending contempt. Whatever differences we may have later, can we agree that the principle behind democracy is to place what is common to all people above what an organization, institution, or group can claim?

This does not call into question the rights of those who benefit from superior natural talents, specialized knowledge, technical competence, or those of institutional organizations: all can, under democratic control, play a useful role in the human economy. But democracy is about giving authority to the whole rather than to the part; and only living human beings are, as such, an authentic expression of everything, whether they act alone or by helping each other out.

From this central principle comes a range of ideas and related practices that history has long demonstrated, although they are not found in all societies, or at least not to the same degree. These elements include: collective self-government, free communication between equals, ease of access to shared knowledge, protection from arbitrary external controls, and a sense of individual moral responsibility when conduct affects the whole community.

All living organisms have a certain degree of autonomy, insofar as they conform to their own form of life; but in humans, this autonomy is the essential condition for their development. When we are ill or disabled, we give up some of our autonomy: but giving it up on a daily basis, and in everything, would transform our very life into a chronic illness.

The best possible life — and here I am fully aware that I am opening a debate — is a life that requires more self-organization, expression and self-fulfilment. In this sense, personality, formerly the exclusive attribute of kings, belongs to all men by virtue of the democratic principle. Life, in its fullness and integrity, cannot be delegated.

In formulating this provisional definition, I hope that in the name of consensus, I have not forgotten anything important. Democracy — I will use it in the primitive sense of the term — necessarily occurs mainly in small communities or small groups, whose members have frequent personal contacts, interact freely and know each other personally. As soon as it involves a large number of people, democratic association must be completed by giving it a more abstract and impersonal form.

As historical experience shows, it is much easier to destroy democracy by creating institutions that will give authority only to those at the top of the social hierarchy than to integrate democratic practices into a well-organized system, run from a center, and which reaches its highest degree of mechanical efficiency when those who work there have no personal will or purpose.

The tension between small-scale association and large-scale organization, between personal autonomy and institutional regulation, between remote control and diffuse local intervention, now puts us in a critical situation. If we had been lucid, we might have understood long ago that this conflict was also deeply rooted in technology.

How I wish I could describe the technique with the same hope of getting your approval as for my definition of democracy, regardless of your reservations and doubts! But I must admit that the title of this article is itself controversial; and it is impossible for me to further my analysis without resorting to interpretations that have not yet been sufficiently disseminated, much less extensively discussed or criticized and evaluated rigorously.

To put it bluntly, the thesis I defend is this: from the end of Neolithic times in the Middle East, to the present day, two techniques have periodically existed side by side, one authoritarian and the other democratic; the first emanating from the center of the system, extremely powerful but by nature unstable, the second emanating from the center of the system, extremely powerful but by nature unstable, the second, human-directed, relatively weak, but ingenious and sustainable. If I am right, unless we radically change our behavior, the time is near when what we have left of our democratic techniques will be completely suppressed or replaced, and so any residual autonomy will be annihilated or only allowed to exist in perverse government strategies, such as national elections to elect leaders already chosen in totalitarian countries.

The data on which this thesis is based is well known; but I think their importance has been overlooked. What I would call democratic technique is the small-scale method of production, based primarily on human skill and animal energy, but always actively directed by the artisan or farmer; each group refining its own talents through arts and social ceremonies that suit them, while making moderate use of the gifts of nature. This technique has limited ambitions, but, precisely because it is widely distributed and requires relatively little, it is very easily adaptable and retrievable. It is this democratic technique that has underpinned and strongly supported all historical cultures up to our time, and it is it that has corrected the perpetual tendency of authoritarian techniques to misuse their powers. Even for peoples forced to pay tribute to the most aggressive authoritarian regimes, in workshops and farmyards, a certain degree of autonomy, discernment and creativity could still be enjoyed. The royal club, the slave leader's whip, and bureaucratic orders left no trace on the textiles of Damascus or the pottery of fifth-century Athens.

While this democratic technique dates back as far as the primitive use of tools, the authoritarian technique is a much more recent achievement: it emerged around the fourth millennium BC, in a new configuration of technical invention, scientific observation, and centralized political control that gave birth to the way of life that we can now identify with civilization, without praising it. Under the new institution of royalty, activities that had previously been disseminated, diversified, tailored to man, were brought together on a monumental scale in a kind of new mass organization that was both theological and technical. In the person of an absolute monarch, whose word had the force of law, the cosmic powers descended to earth, mobilized and unified the efforts of thousands of men, who had hitherto been far too autonomous and independent to voluntarily grant their actions for purposes beyond the village horizon.

This new authoritarian technique was not hampered by village custom or human feeling: its herculean prowess of mechanical organization was based on relentless physical restraint, forced labor, and slavery, which spawned machines capable of providing thousands of horsepower several centuries before the invention of the horse harness or the wheel. High-order scientific inventions and discoveries inspired this centralized technique: the paper trail through reports and archives, mathematics and astronomy, irrigation and channeling; and above all the creation of complex human machines composed of interdependent, replaceable, standardized and specialized parts — the army of workers, the troops, the bureaucracy. Workers' armies and troops raised human achievements to hitherto unimaginable levels, in large-scale construction for the former and in mass destruction for the latter. In its territories of origin, this totalitarian technique was tolerated, even desired, despite its continuous propensity to destroy, because it organized the first regulated economy of abundance: in particular immense food crops that not only provided food for a large urban population, but also freed up a large professional minority for military, bureaucratic, scientific or purely religious activities. But weaknesses that have never been overcome until our time were reducing the effectiveness of this system.

First of all, the democratic economy of the agricultural village resisted being incorporated into the new authoritarian system. That is why, after breaking the resistance and collecting the tax, even the Roman Empire considered it appropriate to grant a great deal of local autonomy in matters of religion and government. Moreover, as long as agriculture absorbed the work of some 90% of the population, mass technology was applied mainly in populated urban centers. Because authoritarian technology first took shape at a time of metal scarcity, and because human raw material, thanks to war captures, was easily transformed into machines, its leaders never bothered to invent mechanical and inorganic substitutes. But it had other weaknesses, even more serious. This system had no internal coherence: all it took was a break in communication, a missing link in the chain of command, for the great human machines to disintegrate. Finally, the myths that underpinned the entire system — and in particular the fundamental myth of royalty — were irrational because of their paranoid suspicions and animosities and their paranoid claims to unconditional obedience and absolute power. Despite all of its impressive constructive achievements, the authoritarian technique reflected a profound hostility to life.

At this point in my brief historical digression, I think you can clearly see where I am coming from: namely, that authoritarian techniques are reappearing today in a cleverly perfected and extremely reinforced form. So far, confident in the optimistic principles of nineteenth-century thinkers like Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer, we have seen the development of experimental science and mechanical inventions as the best guarantee of a peaceful, productive, and above all democratic industrial society. Many people, to reassure themselves, chose to think that there was a causal relationship between the revolt against arbitrary political power in the seventeenth century and the industrial revolution that accompanied it.

But it turns out that what we have interpreted as the new freedom is a much more sophisticated version of the old slavery: because the emergence of political democracy over the past few centuries is increasingly being neutralized by the accomplished resurrection of centralized authoritarian techniques — a technique that had been relaxed in many parts of the world.

Let us not be taken advantage of any longer. At the very moment when Western nations were overthrowing the old absolutist regime, governed by a king formerly of divine essence, they were restoring the same system in a much more effective form of their technique, reintroducing military constraints, no less draconian in the organization of the factory than in the new organization of the uniformed and rigorously trained army.

During the last two centuries, which constitute transitional stages, one could be perplexed by the final orientation of this system, because there was strong democratic resistance in many places; but with the unification of scientific ideology, itself freed from the limits imposed by theology and the ends of humanism, the authoritarian technique had at its fingertips an instrument that now gives it absolute control of physical energies of cosmic dimensions.

The inventors of atomic bombs, space rockets and computers are the pyramid builders of our time: their psyche is deformed by the same myth of unlimited power, they boast of the omnipotence, if not omniscience, that their science guarantees them, they are agitated by obsessions and impulses no less irrational than those of previous absolutist systems, and in particular this notion that the system itself must expand, regardless of the ultimate cost to living.

Through mechanization, automation, cybernetic organization, this authoritarian technique has finally succeeded in overcoming its most serious weaknesses: its original dependence on resistant and sometimes actively undisciplined servomechanisms, still human enough to aspire to ends that are sometimes contradictory to those of the system.

Like its primitive version, this new technique is wonderfully dynamic and productive: its power in all its forms tends to increase unlimitedly, in proportions that defy the power of assimilation and prevent any control, whether in the productivity of scientific knowledge or in that of industrial assembly lines.

Bringing energy, speed, and automation to their maximum development, without worrying about the diverse and subtle conditions that support organic life, has become an end in itself. And judging by national budgets, as in the first forms of authoritarian techniques, all the effort is focused on totalitarian instruments of destruction, designed for totally irrational purposes whose main effect would be the mutilation or extermination of the human race. Even Ashurbanipal and Genghis Khan carried out their bloody enterprises within the bounds of human normality.

In this new system, the center of authority is no longer a distinct personality, an all-powerful king: even in totalitarian dictatorships, the center is now within the system itself, invisible, but omnipresent; all its human components, including the technical and ruling elite and the sacred scientific priesthood, which alone has access to the secret knowledge that will allow total control, are also trapped by the very perfection of the organization that they invented.

Like the Pharaohs of the Pyramid Age, these servants of the system identify its benefits with their own well-being; like the god-king, their apology for the system is an act of self-worship; and like the king again, they are plagued by an irrepressible and irrational need to expand their means of control and push the limits of their authority. In this collective at the center of the system, this Pentagon of power, no visible presence gives orders: unlike Job's God, we cannot face the new deities, let alone oppose them.

Under the pretext of reducing work, the ultimate goal of this technique is to evict life, or rather to transfer its properties to the machine and the mechanical collective, legitimizing only that part of the organism that can be controlled and manipulated.

Make no mistake about this analysis. The danger to democracy does not come from specific scientific discoveries or electronic inventions. The human impulses that dominate authoritarian techniques today date back to a time when the wheel hadn't even been invented yet. The danger comes from the fact that, since Francis Bacon and Galileo defined the new goals and methods of technology, our great physical transformations have been accomplished by a system that deliberately eliminates human personality in its totality, ignores the historical process, ignores the historical process, exaggerates the role of abstract intelligence, and makes the dominance of physical nature, and ultimately of man himself, the main purpose of existence. This system has penetrated Western society so insidiously that my analysis of its misuse and its purposes may actually seem more questionable — more shocking in truth — than the facts themselves.

How can we explain that our era has given itself up so easily to controllers, manipulators, and developers of authoritarian techniques? The answer to this question is both paradoxical and ironic.

The current technique differs from that of the systems of the past, which were openly brutal and absurd, in one particular detail that is highly favorable to it: it has accepted the basic democratic principle under which every member of society is supposed to enjoy its benefits. It is by progressively fulfilling this democratic promise that our system has acquired total control over the community, which threatens to annihilate all other democratic remnants.

The deal offered to us is presented as a generous bribe. Under the terms of the democratic-authoritarian social contract, each member of the community can claim all the material benefits, all the intellectual and emotional stimulants that they may desire, in proportions hitherto just accessible even to a small minority: food, housing, rapid transport, rapid transport, instant communication, medical care, entertainment and education. But only on one condition: not only that we do not require anything that the system cannot provide, but that we also accept everything that is offered, duly processed and produced artificially, homogenized and standardized, in the exact proportions that the system, and not the person, requires. If one chooses the system, no other choice is possible. In a nutshell, if we abdicate our lives in the first place, the authoritarian technique will return to us everything that can be mechanically calibrated, multiplied quantitatively, manipulated, and collectively amplified.

“Isn't that a fair deal? will ask those who speak for the system. “Aren't the benefits that authoritarian technology promises real? Isn't this the cornucopia that humanity has dreamed of for so long, and that all the ruling classes have tried to appropriate, with all the brutality and injustice that is necessary? ” Above all, I would not want to deny that this technique has created many admirable products, or to denigrate them, because a self-regulated economy could make good use of them.

I just want to suggest that it is time to take stock of the human costs and inconveniences, not to mention the dangers, to which our unconditional adherence to the system itself exposes us. Even the immediate costs are high, because this system is so far from being subject to effective human direction that it could poison us en masse to feed us or exterminate us to ensure our national security before we can enjoy its benefits.

Is it humanly beneficial to give up the possibility of spending a few years at Walden Pond[1] For the privilege of spending a lifetime in Walden Two[2] ? When our authoritarian technique has consolidated its power, thanks to its new forms of mass control, its array of tranquilizers, sedatives, and aphrodisiacs, how can democracy survive? It is a stupid question: life itself will not withstand it, except what the collective machine will tell us.

An aseptic scientific intelligence spreading across the planet would not be the happy culmination of divine design, as Teilhard de Chardin so naively imagined, it would rather be the definitive condemnation of all new human progress.

Again, don't get me wrong about what I mean. I am not predicting a certain future, but I am warning of what may to happen.

What should we do to escape this fate? In describing the authoritarian technique that attempts to dominate us, I did not forget the great lesson of the story: “Be prepared for the unexpected! ” Nor am I unaware of the immense reserves of vitality and creativity that a more humane democratic tradition still has at our disposal. I want to persuade those who care about maintaining democratic institutions that their efforts in this direction must also include technology. It is also a question of putting man back at the center.

We must oppose this authoritarian system that gives an underdeveloped ideology and technology the authority that belongs to the human personality. I repeat: life cannot be delegated.

Singularly and in a deliciously appropriate symbolic way, the first quotation in support of this thesis came from an agent who was well disposed to this new authoritarian technique — making it almost the archetype of the victim! This is the astronaut John Glenn, whose life was endangered because of the malfunction of his automatic controls, activated remotely. After narrowly saving his life thanks to his own intervention, he emerged from the space capsule by exclaiming: “Let man take control from now on! ”

Which is easier said than done. But if we don't want to be forced to take even more drastic measures, like those mentioned by Samuel Butler in Erewhon[3], we would be well advised to consider a more constructive solution: namely, the reconstitution, of both our science and our technology, so as to be able to introduce, at each stage of the process, those aspects of the human personality that were excluded from it.

This means sacrificing quantity alone without regret in order to restore the possibility of qualitative choice; it is necessary to transmit authority, currently in the hands of the collective machine, to the human personality and the autonomous group; preference must be given to ecological variety and complexity instead of accentuating excessive uniformity and standardization; and above all, it is necessary to weaken the drive that makes the system grow instead of containing it firmly in human limits, and thereby liberate man to allow him to pursue other purposes.

The question we need to ask ourselves is not what is good for science, much less for General Motors, Union Carbide, IBM or the Pentagon, but what is good for humans: not the man of the masses, subject to the machine and regimented by the system, but man as a person, free to move in all areas of life.

The democratic process can recover large parts of technology, if we overcome the childish impulses and automations that now threaten to cancel out all that we have acquired that is truly positive. The very leisure that the machine provides in advanced countries can be used profitably, not to be subservient to other machines that offer mechanized relaxation, but to undertake tasks whose meaning and scope are neither profitable nor technically possible in a system of mass production: tasks that require a particular talent, knowledge, and aesthetic feeling. The DIY movement stalled prematurely because it tried to sell even more machines, but its slogan was just right.[4], provided you still have a self that can make use of it. We will only be able to overcome the glut of cars that clog and destroy our cities by redesigning these cities in order to promote a more effective human agent: the walker. And if we consider birth and delivery, we are thankfully seeing a regress from the unwelcome, often lethal, authoritarian procedure, centered on hospital routine, in favor of a more humane process that gives back the initiative to the mother and to the body's natural rhythms.

Complementing and enriching democratic technology is obviously too important a subject to be dealt with in one or two concluding sentences: but I hope to have clearly demonstrated that the authentic advantages of science-based technology can only be maintained if we go back in time, to a point where man can have a choice, intervene, make projects for purposes entirely different from those of the system.

In the current circumstances, if democracy did not exist, we would have to invent it in order to preserve the character and genius of man and to start perfecting it again.

Lewis Mumford