The latest book by anarchist theorist and activist Peter Gelderloos contains a number of highly relevant analyses of the nuisance that state-controlled corporations represent. In Strategies for an Ecological Revolution from Below (2022), he rightly criticizes the use of « green » energies, nuclear power, and other false solutions such as the Green New Deal and the eco-Leninism of an Andreas Malm, the racist concept of Anthropocene and Jared Diamond's lies about the "right" government. Gelderloos also shows that statist societies have always destroyed the environment contrary to tribal societies, who keep today 80% of biodiversity on their lands[1]. However, despite its undeniable qualities, the book remains superficial on technology, industry and the dynamics of international relations, and downright mediocre when it comes to strategy. In fact, Gelderloos has not written a book of "strategies", but of critical thinking that lists a few effective tactics for stopping one industrial project at a time.

As a reminder, strategy is a general, evolving, flexible and adaptable plan that guides an organization's actions to achieve a goal. You won't find anything like it in Gelderloos' book. After reading it, we still don't know how to bring down industrial capitalism. On the contrary, Gelderloos seems to reject any form of theoretical homogeneity in a rather dogmatic and irrational way. For example, he explicitly states that an eco-anarchist movement must reject uniformity of point of view, which is tantamount to rejecting the adoption of a precise goal and a roadmap to reach it. Because of this kind of theorizing, decentralized eco-anarchist movements are conspicuous by their ineffectiveness in stopping the system that is devastating the planet. It's quite despairing to see experienced activists fall back into the same trap that was criticized by Nestor Makhno and other anarchist theorists over a century ago (see later in the article).

Strategy of attrition vs. strategy of cascading failure

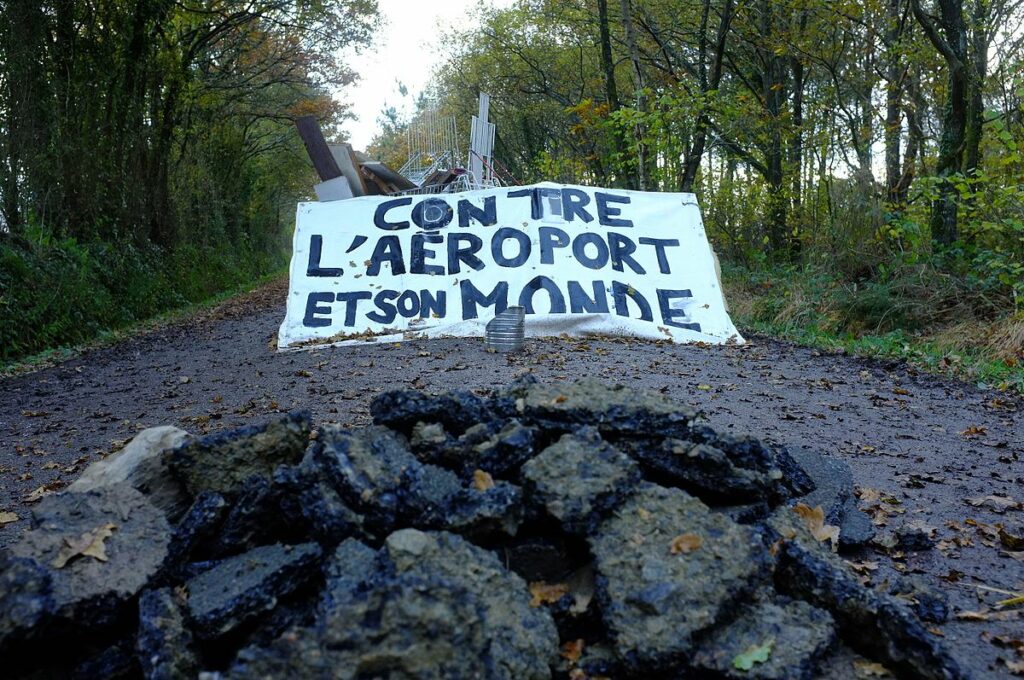

At the start of chapter 3 entitled "The solutions are already here", a lucid reader about the state of the world can only be surprised to learn that "the victories are adding up" and that "we are stopping pipelines, airports, highways and mines". Although industrial projects are halted from time to time, the vast majority continue to be completed. Globally, we continue to lose. Global CO2 emissions continued to rise in 2022[2]. In 2020, the industrial system passed the milestone of more than 100 billion tons of material removed from the earth's crust[3]. The system covers more than 20 million hectares a year with concrete and bitumen, equivalent to twice the surface area of Portugal[4].

The tactics listed by Gelderloos - blockades, sabotage, land occupations, etc. - which target one project at a time, are employed as part of a strategy of war of attrition. This strategy is best employed if you have abundant resources at your disposal. This is not the case for the underdog camp in an asymmetrical conflict. As a Stop Fossil Fuels article explains so well, "We react defensively" to the attacks of the industrial system. The problem is that "we oppose one destructive project at a time", and clearly "we’re losing[5]". We need to study the industrial system, find its weak points and hit it where it hurts. If we take the example of land occupations, they will never be viable in the long term without first considerably diminishing the ability of industrialized states to use their power both within and beyond their borders.

The intersectional impasse

In the chapter entitled "Versatile strategies", Gelderloos lists the "common characteristics" of the movements that make up global environmental resistance (South and North). In particular, he notes the great heterogeneity of these movements. So Gelderloos advocates heterogeneity. We could be delighted. A diverse movement, made up of people from different social and cultural backgrounds, each bringing their own skills and experience, tends to be more resilient and effective than a homogeneous one. Gelderloos also rightly contrasts the heterogeneity of the revolutionary movement with the out-of-touch technocratic vision that seeks to impose a homogeneous solution on a territory made up of protean communities. But Gelderloos goes even further, rejecting any form of theoretical unity within the revolutionary movement. As an example, he cites the Zapatistas, who according to him, have formed an “extremely heterogeneous” movement. But the Zapatistas had some theoretical unity. Their main demands were land reappropriation and political and cultural autonomy for the indigenous populations of Chiapas and the rest of Mexico[6]. And even in effective so-called “decentralized” movements, there are leaders, organizers and a certain unity of purpose, which Western idealists tend to gloss over when they talk about Chiapas or Rojava. It's impossible to organize and work together - and thus bring a revolution to fruition - without unity of perspective.

In his list of “characteristics”, Gelderloos claims that all the groups making up the global environmentalist uprising would be intersectional.

“The movements involved in this uprising tend to move beyond limited visions, focused on a single issue. Instead, they recognize the interconnectedness of different forms of oppression and, as a result, respect a principle of solidarity.”

Basically, for Gelderloos, indigenous peoples around the world in struggle against industry and the state would be applying the principles of the Western deconstructed left (identitarianism, individual actions, endless multiplication of goals, horizontal hostility, etc.). According to him, revolutionary groups such as the EZLN, MEND, YPG, BRA, FARC, Nagas, Zomia tribes and indigenous resistance in North America[7] have been or are intersectional. Each individual participating in these movements would define his or her own oppressions and wage his or her own struggles, “thus neutralizing any ambition to impose uniform solutions.” This approach would even be one of the main reasons for the success of some of these movements... We could laugh about it if what was at stake wasn't the future of life on Earth.

The fact that Gelderloos can't appreciate the limits of dogmatic intersectionality is symptomatic of his lack of strategic vision[8]. Anarchists[9] and Marxists[10] everywhere denounce the reformist recuperation of intersectionality as horizontal hostility diverting attention from the material infrastructure of the system.

But Gelderloos is confused in other ways. He states that :

“anarchism doesn't involve converting everyone to my way of thinking. It's about a methodology for building a world in which a thousand worlds can find their place.”

Not to convert? That's exactly what the priests of the intersectional Church are trying to do. Everyone wants to impose their morality on everyone else, provoking recurrent conflicts. Divide and conquer benefits the techno-industrial system and a few left-wing intelligentsia figures, who bear a heavy responsibility for the rise of fascism.

Another problem. Without a radical rejection of industrialism, of the industrial system as a whole, its factories and its machines, the “thousand worlds” Gelderloos envisions have no chance of emerging. You can't claim to be an anarchist and at the same time defend industrialism. In fact, perhaps Gelderloos should reread the testimonials he collected for his book, particularly the one in which two Guaraní women say that “the advance of technology is distancing many young people from their culture”. The links between the cultural standardization of the world and technological progress were observed very early on by Stefan Zweig[11], then by Claude Lévi-Strauss[12], Jacques Ellul[13] and more recently by sociologists such as Joseph Tonda[14]. NGOs are warning of the extinction of “biocultural[15]” diversity. Low and Harmon even published a study in 2014 blaming “technological progress” in transport and communication infrastructures for an acceleration in the process of “linguistic transfer[16]”.

Irrational rejection of unity of perspective

As an idealist, Gelderloos prefers to dream of the world of tomorrow rather than think about the material means of destroying today's world. His rare “strategic” reflections allow us to anticipate bitter defeats for any movement that applies them. In a sub-section of chapter 4 entitled The ecological revolution: the best strategy to win or fail, Gelderloos quotes an anarchist essay entitled 23 Theses Concerning Revolt, which rejects objective reality, rationality, the division of society into classes and, unsurprisingly, any form of strategy. Reading between the lines, we understand that the author rejects the very idea of forming a revolutionary movement. (The passage in bold does not appear in Guelderloos' book).

"All military strategy is to impose an ideal plan on the map that represents reality. Anarchy, not as a revolutionary movement, but as a multifaceted reality of rebellion and permanent creation, is based on the free initiative of every member of society; in the idea that we all contemplate social problems with our own eyes, and not from above. Many of the divisions that have affected the anarchists with the passing of the decades have been revealed as totally incoherent with the ideal of anarchy, because they are based on the pretension of creating a compulsory unity. I am referring to the complaint that one is not following the plan, that one is not doing with her resources what she should do.

If we do not intend to make a military campaign, we must refuse to see the revolution as something organized according to a unified plan, as if it were a game of Risk. We are not looking down from above, giving orders. We are here, in the midst of a beautiful chaos that our enemies always try to organize. We will be stronger than ever if we learn to triumph in this chaos, to move in the network of our own relationships, to communicate horizontally or circularly, to use only what really is ours and to influence others, to understand that not everyone is going to act as we act; that is the beauty of rebellion, and our effectiveness in it does not lie in making the whole world equal, but in devising the best way to relate in a complementary way to those who are different and follow different paths."

When Gelderloos cites a text that celebrates disorganization and "chaos" as a reference, it's easy to understand the strategic and organizational nothingness of his work. He goes on to say:

“We need to perceive “an ecosystem of revolt” in which, instead of trying to control what everyone is doing, promote the right ideas and suppress the wrong ideas, we understand our niche and create relationships of reciprocity with those around us, making us all stronger and healthier rather than making us all the same.”

Better to let people carry on with bad ideas. Better to let them waste their time, money and energy pedaling in the mud than carrying out effective revolutionary action. Let's forget militant exhaustion is a scourge that gangrenes our camp and turns revolutionaries away from the struggle. What people like Gelderloos say is wildly irresponsible in the face of the countless dangers that threaten us.

Does debilitating individualism make us collectively stronger? Obviously not, since in the West we are losing the overwhelming majority of our struggles. What's more, it's not excess but lack of theoretical unity that plagues revolutionary movements. It's the lack of theoretical unity that killed the Gilets jaunes, and it's what's preventing the environmental movement from gaining momentum. z

Historian Alexandre Skirda reminds us, citing Makhno and Archinov, that the infantile individualism of certain anarchists was already posing problems for building a solid revolutionary force[18].

"The publication la Plate-forme continues in subsequent issues of the magazine. What is its content? The arguments put forward in Diélo trouda's first articles are taken up and developed. The main cause of the anarchist movement's failure lies in the "absence of firm principles and consistent organizational practice". Anarchism must "rally its forces into an active general organization, as required by the reality and strategy of the social class struggle", in line with the Bakuninist tradition and Kropotkin's wishes. This organization would establish a general tactical and political line for anarchism, leading to "organized collective practice"."

In the same book, Skirda quotes Nestor Makhno, who is indignant at the irresponsibility of "chaos" enthusiasts like Gelderloos.

"We expected the idea of organized anarchism to meet with stubborn resistance from the partisans of chaos, who are so numerous in anarchist circles, because this idea obliges every anarchist who participates in the movement to take responsibility and to pose the notions of duty and constancy. Whereas the favorite principle in which most anarchists up to that point had educated themselves can be expressed by the axiom: "I do what I want, I take nothing into account." It is only natural that anarchists of this kind, imbued with such principles, should be violently hostile to any idea of organized anarchism and collective responsibility."

Makhno goes on to point out that anarchists are not in the business of building the societies that will emerge after the dismantling of the state. Their mission is to direct the revolutionary movement to free people from the yoke of the state, nothing more, nothing less.

"Anarchists will lead the masses and events from a theoretical point of view. The action of leading revolutionary events and the revolutionary movement of the masses must not and cannot in any way be conceived from the point of view of ideas, as an aspiration on the part of anarchists to take the building of the new society into their own hands. This task belongs to laboring society alone, and any attempt to take this right from it must be considered anti-anarchist. The question of idea leadership is not a question of socialist construction, but of theoretical and political influence on the revolutionary march of political events. We wouldn't be revolutionaries or fighters if we didn't take an interest in the character and tendency of the revolutionary struggle of the masses. And, since the character and tendency of this struggle are determined not only by objective factors, but also by subjective elements, i.e. by the influence of various political groupings, our duty is to do everything possible to ensure that the ideological influence of anarchism on the course of the revolution is pushed to the maximum.

The current "epoch of wars and revolutions" poses with exceptional acuteness the main dilemma: whether revolutionary events will evolve under the influence of state ideas (even socialist ones), or under the influence of no-state ideas (anarchism).”

Techno-confusionism

Many passages in the book also reveal Gelderloos's lack of technocritical culture. What emerges is a great deal of confusion. For example, he refers to "horizontal technologies" without clearly defining how they differ from "vertical" technologies. Clearly, Gelderloos seems to believe that technology is politically and socially neutral. Not every technology in itself contains politically and socially perverse effects. All we have to do is expropriate the evil capitalists, and technology will instantly become virtuous.

"Every technology that is not entirely under our control, entirely extirpated from the capitalist market and colonial institutions, is a weapon pointed at us and at the planet."

A giant self-managed excavator is no longer a "weapon pointed at us and the planet". It would therefore be possible and even desirable to reappropriate chemical factories (to produce medicines), power plants, cargo ships or even the Internet. Gelderloos recycles the fable of self-management of the industrial system in a green, degrowthist sauce. For him, capitalism, not industrialism, is the problem.

"Industrialism is an obvious candidate [for global ecological collapses], but to blame smokestacks and fossil fuels is to confuse cause and effect."

From a materialist perspective, it should be obvious that it was the technical advances of the Industrial Revolution that enabled capitalism to become thermo-industrial, and to exponentially increase its destructive power. The mass of buildings and infrastructures of industrial civilization exceeds that of all living beings on Earth[19]. And to maintain them, to keep them in working order, billions of tons of material have to be extracted from the earth's crust every year[20], whether the economy is capitalist or communist. It's a question of mechanics, one would say.

For Gelderloos, "the cause of the global ecological crisis is colonialism." Here again, we are perplexed by such absurdities. Colonialism is not a cause but a consequence - or rather, a condition of existence - of urban societies, which are always the product of statist, hierarchical, unequal and authoritarian societies. Demographic concentration has always been a technique employed by state elites to deprive rural populations of their autonomy[21]. But Gelderloos naively believes that it is possible and desirable to self-manage a large modern city like New York, whose very existence is based entirely on the industrial system that is destroying the planet and its indigenous peoples.

We recall in passing the figures of geographer Guillaume Faburel:

“On a planetary scale, cities, which represent only 2% of the Earth's surface, are already responsible for 70% of waste, 75% of greenhouse gas emissions, 78% of energy consumption and 90% of air pollutants[22].”

Preventing genocide without dismantling the system that makes it possible

Later in the book, Gelderloos also wants to "make sure that mass murder doesn't pay". A laudable goal, but until the techno-industrial system is dismantled, increasingly powerful technologies will continue to be produced and disseminated (AI, nanotechnologies and biotechnologies, for example). As a result, mass murder becomes more accessible to states, corporations, terrorist or paramilitary groups, political parties, religious sects or isolated individuals. Sebastián Cortés also believes that fascism is a germ of industrial society[23]. As for historian Zygmunt Bauman, he has noted the structural links between the growing power of technology, the development of modern states and genocide[24].

Idealism leads to immobility

Gelderloos's patent idealism reaches its climax when he tries to imagine the Catalan territories once "global capitalism" has been dismantled. As the state weakens, he wants to use the remaining fuel reserves to run cargo ships from wealthy to vulnerable poor regions. The aim: to send food and machinery parts so that "the poorest regions can achieve self-sufficiency in the production of food, medicine and all other vital goods." This "worldwide transfer of resources" will be achieved "through union organization in ports and factories".

"All medicines, all scientific research, all machine plans, all codes were immediately made universally accessible."

Basically, Gelderloos wants to do what the big neo-colonialist humanitarian NGOs are already doing. International solidarity is the best alibi for maintaining the global techno-industrial system, and thus the domination of the North over the South.

In Gelderloos' fable, territories reach self-sufficiency in just a decade. From the leaders' point of view, "it was an apocalyptic collapse". But "for the rest of us, and even if it has not been without great difficulties, it has been the greatest victory we have ever known." Gelderloos seems to believe that his revolution would have the capacity to solve, in just a few years, most of the problems that have plagued this world for centuries.

And Gelderloos continues his stroll through his utopian world. According to him, "a tacit consensus within this growing network of self-governing territories was to plug all oil and gas wells as quickly as technically possible, except when this risked causing famine". If it risks causing famine, we keep on killing the climate! In such a situation, "the entire network would commit to helping the territory in question adapt its food infrastructure to free it from its dependence on fossil fuels." Because, of course, once capitalism collapses, there will magically be an immediate convergence of the interests of every human being on the planet. Humanity will become one, mutual aid will become universal, and so on. Like many alterglobalists, Gelderloos refuses to accept the material reality of this world. For example, the fact that the neurological capacities of the human brain are limited. Indeed, we are incapable of feeling empathy for millions of people at once[25].

Gelderloos wants to restore wetlands, forgetting to mention that this will encourage the establishment of mosquitoes that are potentially vectors of deadly epidemics[26]. Rural and urban people live in peace and harmony, because the problem was the state, not the city itself as a material structure and social organization:

"Suddenly, the city became a happy meeting place belonging to its own inhabitants. With the abolition of the police, title deeds were burned and everyone had access to adequate housing overnight."

For Gelderloos, it's only the "police" and "fascist paramilitaries" that need to be abolished. He probably imagines that drug dealers and religious extremists are reasonable people who will naturally embrace the eco-anarchist revolutionary ideal. In agriculture, "harvesting is done with tractors running on biofuels", or manually, but only when people are "highly motivated". He hopes to avoid supermarket shortages by self-managing the entire agri-food circuit, from fields to factories to distribution.

"Taken out of the global production network for profit, factories have either been abandoned or taken over by their workers."

Most factories are "reallocated to meet social needs" and "only operate a few days a week". As if a factory could be freely self-managed. And who works in the factories? Simple, "those with an affinity for big machines" (i.e. engineers, technicians, managers) and "volunteers who can put up with the noise and artificial environment" (i.e. workers). Note how Gelderloos still relies on volunteers to carry out the most thankless tasks, wiping out with a wave of the hand everything that technocracy has put in place to make the industrial system sustainable (widespread dispossession of the means of subsistence, scientific organization of work, corruption of the masses through material abundance, entertainment, etc.). Of course, there will always be a hierarchy in the factory, as workers operate large, complex machines designed by engineers. No industry without technocracy.

The passage on the left-wing Internet is also worth reading, and would be highly valued on a self-managed market.

"There is still a strong shared desire for global communication. Such a communication network is vital for adapting to global problems as well as for ensuring solidarity and resolving conflicts."

Radio and the telephone regain ground, while the gigantic infrastructure of the global Internet is maintained. But Gelderloos advocates degrowth. The volume of data exchanged will be considerably reduced and limited to "international friendships", "sharing scientific articles and news".

Much of the scientific research will focus on "the development of synthetic materials that are neither toxic nor derived from petroleum". As if it were possible to control scientific research and its consequences.

The same goes for the energy system. We get rid of certain power plants at the margins when they are deemed harmful to ecosystems, but we keep them when their dismantling could harm the human communities that depend on them. At this rate, we've got another 1,000 years of industrial capitalism ahead of us.

Everything Gelderloos proposes in his grotesque utopia requires global cooperation that only states, multinationals and large NGOs can organize and coordinate. This utopia is based on industries, heavy machinery, huge energy, transport and communication infrastructures, and therefore on a class society dominated by an elite of technicians. What's more, preserving trade routes between North and South for humanitarian purposes is tantamount to reproducing ad infinitum the system Gelderloos detests.

The best thing to do to stop the carnage and at the same time free the populations of the Global South from the yoke of the West and BRICS[27] is to turn off the energy tap and cut off all transport and communication routes between the two zones. We need to do this without worrying about the short-term consequences, and instead rejoice in the long-term consequences - the salvation of life on Earth and of the human species, the rewilding of immense territories, an explosion of cultural and biological diversity, the great return of wildlife, the possibility for indigenous peoples and our descendants to live with dignity, to taste beauty, to experience freedom.